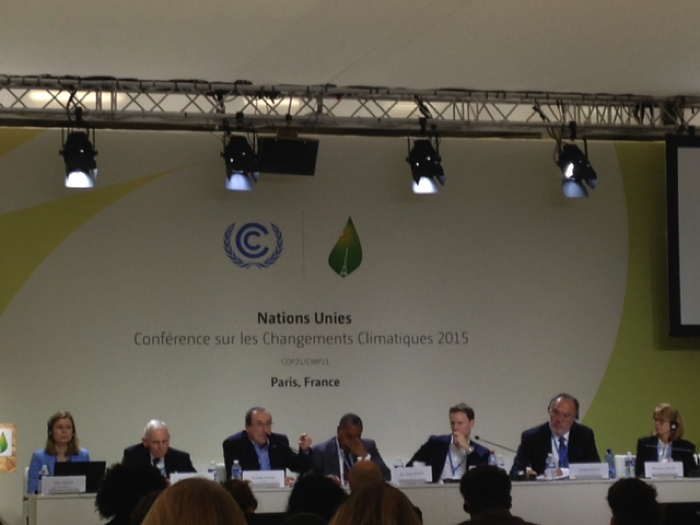

How and to what extent do our leaders and decision-makers need to address migration as a climate change issue? This issue was at the forefront of our minds recently when we had the unique opportunity to attend the 21st annual climate talks, known as the Conference of the Partners (COP21), in Paris, France in November and December of last year.

We participated in COP21 as part of a wider delegation from Minnesota that included past and current Minnesota state representatives, St. Paul Mayor Chris Coleman, and several other representatives from government and non-governmental organizations. Like previous meetings, the goal of COP21 was to convene a meeting of world leaders and to negotiate a global climate treaty, laying the groundwork for preventing global average temperatures from rising no further than a maximum of two degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels.

Because our research focuses on migration and population displacement caused by environmental conditions and climate change, we were invited to attend by the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environment as official observers via the University’s official status with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. We and our fellow colleagues were encouraged to find that the Paris Agreement formally acknowledged the importance of “displacement related to the adverse impacts of climate change,” noting for the first time that “climate change is a common concern of…migrants.”

Migration is an adaptive strategy that is employed by individuals, families, and households in the face of environmental and climate change, and is typically pursued after one or more initial attempts have been made to adapt in one’s place of residence. In other words, migration is often an adaptive strategy of last resort, which is consistent with the fact that migration is a relatively rare demographic event.

In a COP21 panel on natural solutions for coastal resilience in the United States, Dr. Kathryn D. Sullivan, Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and Administrator for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, noted that, worldwide, they expect about a 40% increase in the number of persons living in coastal zones, areas that are vulnerable to sea-level rise and flooding. In some circles, demographic projections of this sort have resulted in some hysteria about the potential for unprecedented numbers of “climate refugees” in the future.

Taking a more nuanced approach, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) convened a panel at COP21 entitled, “Human Mobility & Climate Change,” in which the panelists discussed the need for more contextually-specific understandings of the climate-migration relationship.

A particularly important intermediary pathway in the climate-migration relationship is whether and the extent to which existing livelihoods are disrupted by environmental and climate change, which, in turn, requires detailed understandings of, for example, the agricultural sector, the availability and quality of capital and credit markets to finance agricultural diversification and intensification, and more.

Of course, this pathway operates on the sending side of the equation. As Ms. Michelle Leighton, Chief of the Labour Migration Branch at the International Labour Organization, pointed out during the IOM panel, what is often missing in discussions of the climate-migration relationship is the receiving side of the equation. Specifically, where will persons displaced by environmental and climate change go? How long will they stay? And how will they be incorporated into labor markets, housing, and civic life?

The IOM panel, the only panel on migration and population at COP21, neglected to address the importance of family and social networks for migration. It is well-documented that family and social networks are among the most important facilitators of migration. And, presently, it is an open question if environmental and climate change will exacerbate or ameliorate the salience of these important connections.

While we were encouraged to see references to and discussions of migration and population displacement in several COP21 panels and in the text of the Paris Agreement, we left COP21 with the realization that much still needs to be done. Our guess is that others working in other areas of demography and the social sciences felt the same way.

COP21 achieved what it set out to do. After two weeks of intense talks, world leaders from nearly 200 countries representing about 97% of carbon emissions worldwide agreed to a global climate change accord, known as the Paris Agreement. While by no means perfect, President Obama noted at the conclusion of COP21 that the Paris Agreement provides an important starting point in creating a planet that is “going to be in better shape for the next generation.”

At COP21, research is but one input into a complex set of political calculations and negotiations. Accordingly, given such a crowded stage, it is essential that demographers and social scientists, including those working at the MPC, continue to connect our work to the natural environment, public policy, and related issues in ways that are clear, visible, and digestible to a wide audience.

Photos by Jack DeWaard