Where are all the prostitutes in the census records of London 1881? In her book, Prostitution and Victorian Society: Women Class and the State , Judith Walkowitz says that a 19th century city like London (where prostitution was legal) had one prostitute per 36 inhabitants. Based on the 1881 London population records, that amounts to about 24,000 prostitutes. The coded occupations in 1881 London data, however, show no signs of prostitutes anywhere.

A person’s occupational title conveys a wealth of information about their daily activity, status in society, and overall lifestyle. The coded occupational classification systems seek to inventory occupations of the time period, grouping similar types of work into categories. Despite the usefulness of the streamlined and coded occupational classification, detail is unavoidably lost. Also, classification systems can either overlook or hide certain types of work, particularly activities that are deemed illegal, immoral, or socially undesirable. While prostitution was legal in 19th century England (and is currently legal in England), there is no code for them in the official occupational classification systems of the time. So, how can we find this hidden class of workers?

The North Atlantic Population Project (NAPP) provides information on more than 26 million people in the census of England and Wales in 1881. Historical census data that is no longer restricted by confidentiality requirements is rich with additional detail available in the written strings fields, such as occupation, industry, detailed address, names, and even disability or other characteristics. Several NAPP data sets include transcribed string fields from the occupation field of the census.

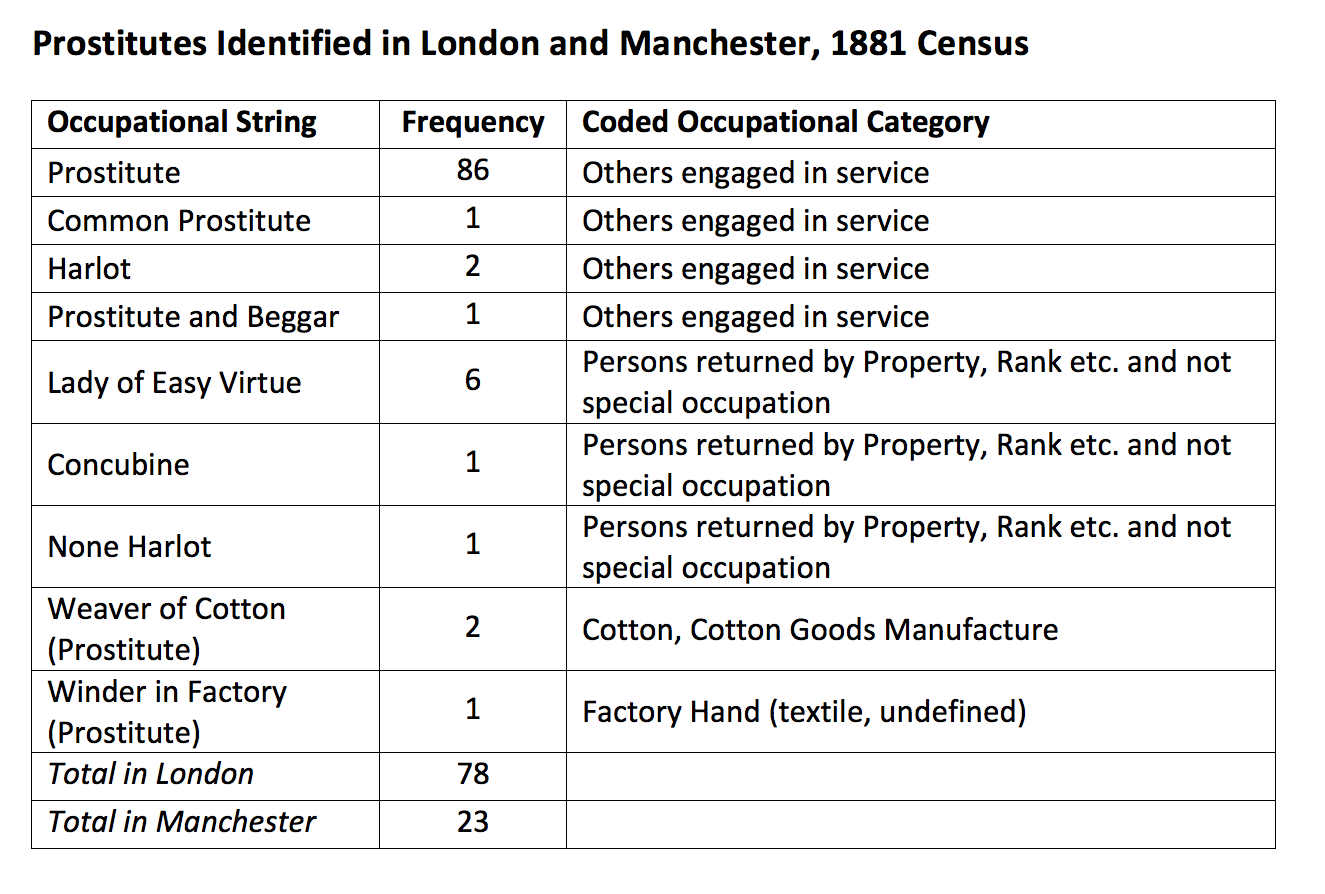

A typical occupational coding scheme will include 300-400 occupational categories. In contrast, data from England and Wales in 1881 includes 1.4 million unique occupation strings (spelling variations, misspellings and odd occupational references included). When listed as “prostitute” in the string field, a person would be classified into the occupational category for “Others engaged in Service” (code 65). This catch-all category includes matrons, couriers, boot cleaners, and office servants in the NAPP database. The strings containing more than just the term “prostitute” provide insight into the types of typical activities of prostitutes. These individuals frequently worked in dressmaking and garment industry factories, in addition to engaging in prostitution. In the later decades of the 19th Century, according to Walkowitz, they were also recruited from the ranks of retail shop girls and waitresses. The table below lists the different ways “prostitutes” are transcribed in the urban areas of London and Manchester in the 1881 census.

Director of the UK Data Archive and the UK Data Service Matthew Woollard explains that the process of census reporting and recording is complex. Census takers visit each house, recording information about the people in the dwelling. Respondents interpret the purpose for the data collection in their own way, leading them to over or under report certain types of activities. Census enumerators also make assumptions or pattern their recording of occupations based on the type of dwelling. In the case of prostitutes, Woollard says that “prostitutes, when incarcerated in prison will often be described as such, however, when on the streets or in brothels they will be hidden under such terms as ‘Milliner’ or ‘Seamstress’ or even ‘Unfortunate.'”

Wollard, Martha Vicinus, and other scholars say that in 1881 England and Wales, a woman likely to be a prostitute was most often young, never married, a native of the country, and living in a collective-style dwelling, such as a boarding house or jail. There are 14,476 women who fall into this category in 1881 London (limiting the age range to between 15 and 25, and defining collectives as dwellings with 30 or more residents). Researchers cannot label them as prostitutes with certainty; some of these women were surely not prostitutes.

At the same time, researchers also miss a number of women who are not living in residences large enough to qualify as collective-style dwellings. Smaller dwellings with many unrelated young women could also be home to potential prostitutes (though those same dwellings would also include women who were not engaged in prostitution as well). In order to draw any conclusions, researchers need additional information, like addresses of known brothels, or more detailed information from external data sources about the residents themselves.

Transcribing string fields from census forms, including occupation and detailed address fields, is a tedious aspect of digitizing historical censuses. However, the additional detail can reveal much about the working population of the North Atlantic countries in the late nineteenth century. Known “cover” or co-occurring professions, household co-resident patterns, type of housing, and neighborhood locations can all aid in locating workers in who are likely to be engaged in underground or illegal professions of various kinds. In the case of prostitutes, we cannot say for certain that any given individual engaged in prostitution, but we can use the additional information from the historical censuses to identify groups who have a high probability of engaging in prostitution.

Story by Sula Sarkar and Lara Cleveland

Thank you to Amanda Koller, whose work, ‘Where Them Girls At:’ Missing Prostitutes From Late 19th Century U.S. and British Censuses, prompted us to dig deeper into the NAPP occupational strings.