By Kari Williams & Isabel Pastoor

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines a household as being food secure when all household members at all times have access to “enough food for an active, healthy life;” it sets a minimum threshold for food security of “ready availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods” and the “assured ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways” (USDA Economic Research Service, 2025). The USDA provides survey modules for assessing food security in the U.S. (see Table 1), which are used in a number of federal surveys.

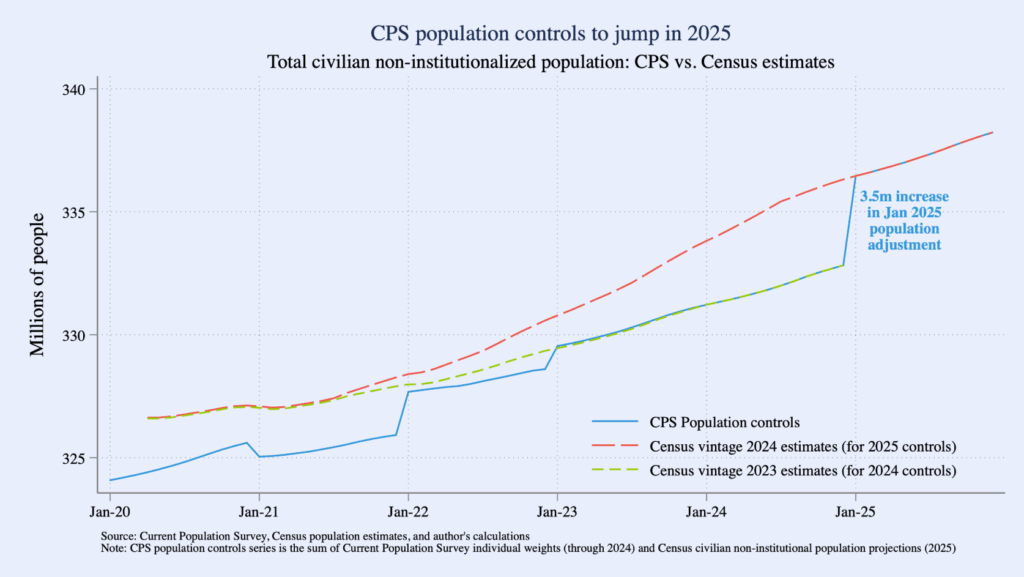

Following the recent announcement by the USDA that they plan to cease data collection for the Food Security supplement fielded as part of the December Current Population Survey, we are highlighting data sources for studying food security in the U.S. Table 2 provides an overview of a number of federal data sources that can be used to study aspects of food security in the U.S. This list of data sources is not exhaustive; we have prioritized data available through IPUMS and other long-running and large-scale population surveys. Additional sources covering shorter time periods or more specific focal populations can be found from the USDA’s Food Security in the United States Documentation page and the Food Access Research Atlas.

According to The DHS Program website, a three-year grant from the Gates Foundation is supporting the dhsprogram.com website and data archive, where researchers apply for access and can download the original public use files. Once a researcher is approved for DHS data access, they can

According to The DHS Program website, a three-year grant from the Gates Foundation is supporting the dhsprogram.com website and data archive, where researchers apply for access and can download the original public use files. Once a researcher is approved for DHS data access, they can