When the Census Bureau announced its recommendation to keep marital history questions in the American Community Survey (ACS) after soliciting comments from the public for 90 days, you may have assumed that demographers everywhere were relieved. And why not? Their retention in the ACS was a major victory for, well, everyone: academics, journalists, statisticians, policy analysts, and anyone with a stake in the history of the two largest program in the federal government, Social Security and Medicare.

But there was troubling news hidden in this announcement: the Bureau’s “deeply flawed” method for evaluating questions is still in place.

Why were questions about marital history targeted for removal, when the American Community Survey is the only reliable source of data to track marriage and divorce in the United States? Some background is necessary to understand the impact and importance of these questions and the data that comes from them, and why the Bureau’s evaluation process must change.

Before the marital history questions were introduced to the ACS in 2008, the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) held the responsibility for national marriage and divorce statistics. These topics were never a priority for the NCHS, however, because collecting and analyzing data on health is its main purpose as an agency. The NCHS stopped formal data collection in 1995, opting to compile raw count numbers of marriages and divorces from states.

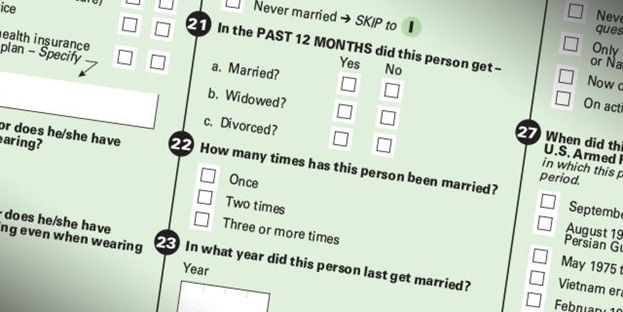

In 2004, at the request of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), the Census Bureau began investigating strategies for collecting marriage and divorce data. After four years, they had devised an accurate, powerful method for measuring marriage, divorce, and widowhood in the United States. This strategy has two main requirements: that the data are collected every year, limiting recall bias, and that a large number of cases are collected. The ACS is the only survey large and regular enough to accommodate this.

Since 2008, in addition to much more reliable information on marriage, divorce, and widowhood, the ACS marital history data have enabled correlation of these important life events with other variables, including work and fertility. This obviously matters a lot to academic demographers, but the impact of this development has been huge: these correlations allow projections of future benefits for Social Security and Medicare.

Why were questions that are so clearly relevant to American taxpayers in danger?

“The Census Bureau adopted a deeply flawed method for assessing the benefits of each ACS question,” Steven Ruggles explained in an open letter in response to the American Commuity Survey content review results. Questions were judged on their “cost” and “benefit,” given scores for each category. The main criteria for a “high benefit” question were “official federal uses for small-area analysis”: 62% of the “benefit” score was derived from federal uses of the question below the state level.

While the marital history questions were judged as “low cost,” they were categorized as “low benefit” because the resulting data are not used for sub-state analysis. As Ruggles reports, “There was no consideration of the number of federal uses of the data, the importance of those uses, federal uses of any small population subgroups not defined by geography, or non-federal uses.”

It’s not just marriage data at stake here. According to the Census review, questions on migration, school enrollment, educational attainment, food stamps benefits, hours worked in the past week, and weeks worked in the past year are all “low benefit,” whereas utility bills and agricultural sales are “high benefit.” This is a senseless way to determine the structure of the nation’s statistical infrastructure, and the current evaluation process should be seriously revised.